what did n.c. contributer to the confederate army

Basics nearly Confederate Uniforms

Fred Adolphus, May 10, 2014, (Updated 21 Dec 2020)

Over the years, I have nerveless information almost the origins and characteristics of the Confederate uniform, and I finally decided to sum this information upwards in a concise article. While many seasoned Confederate buffs might observe this very simplistic, I have been asked questions regarding these topics so oftentimes that I call up this information will be useful for beginners every bit well as experienced uniformologists.

The Confederate compatible origins trace a diverse lineage. The basic color for the coat, grey, comes from the standard American state militia color cadet greyness (which itself was derived from the earlier, medium gray fatigue compatible). Cadet gray came to embody the colour of the "sovereign country" uniform color versus the nighttime blue of the "national government." This association was fundamental to cadet greyness's adoption by the S, given its connotations of state sovereignty. This light shade of blue-gray was not whatsoever darker than the American ground forces sky blue. But American buck grey was not to become "Confederate" greyness. It was too difficult to brand in the South in large quantities, given limitations in resource, such as colour fast dyes, mordants and manufacturing capacity. Instead, the standard British ground forces, darker blue-gray became Confederate gray due to its availability through the blockade. The dark blue-grayness kersey was however referred to as cadet grayness (also oft spelled "grey"). Contemporaries besides called it Amalgamated gray, English army textile, "gray textile," kersey, or any combination of these terms to distinguish information technology from domestic weaves and other shades of gray. Therefore, the Confederate compatible speedily caused British roots, in addition to its American antecedents.

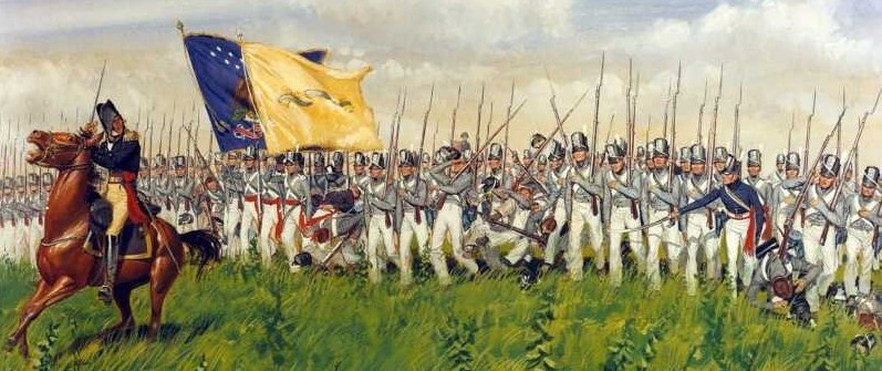

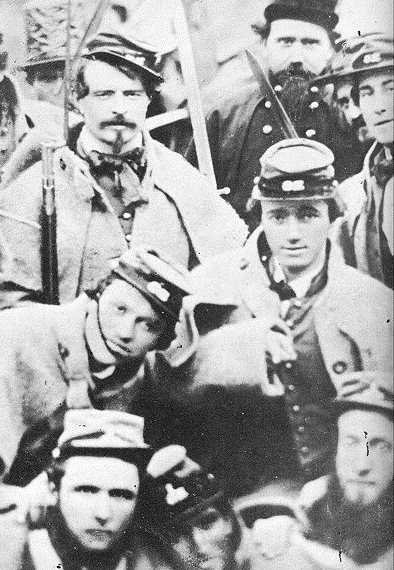

Paradigm 1: The 6th U.Due south. Infantry Regiment at the Boxing of Chippewa wore the gray fatigue jacket, unremarkably used past country militias, instead of the blue tailcoats of the regular army. This caused the British to mistake them for militia, and underestimate their prowess at arms. The American army'due south apply of gray uniforms began about this time. Image courtesy of the U.S. Army.

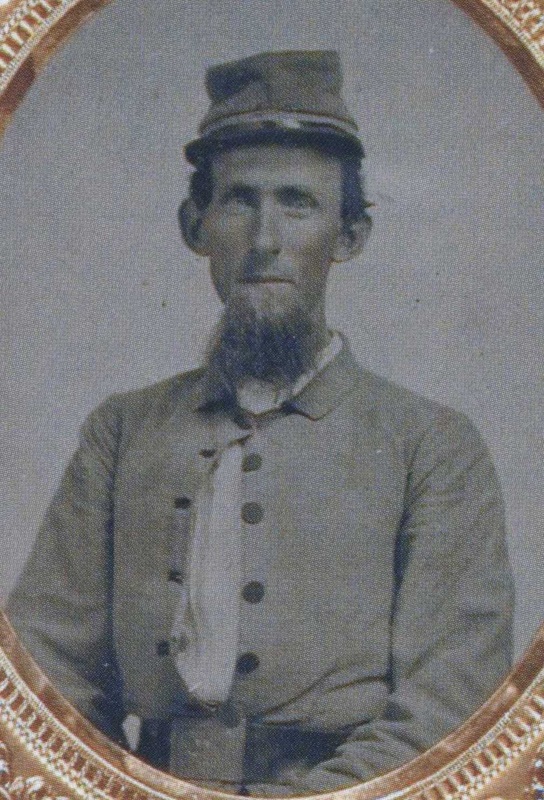

| Epitome two: Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth'due south frock coat reflects the pre-war utilise of buck grey by state forces and its light shade. Artifact and epitome courtesy of the New York State War machine Museum. | Epitome iii: George W. Wilson, 1st Maryland Artillery, CSA wore this cadet gray jacket late in the war. Its darker color contrasts sharply with the lighter, pre-war shade. The dark shade, imported, blue-grey kersey of Wilson'southward jacket reflects what was typical of the Amalgamated army. Artifact courtesy of the Smithsonian Establishment. |

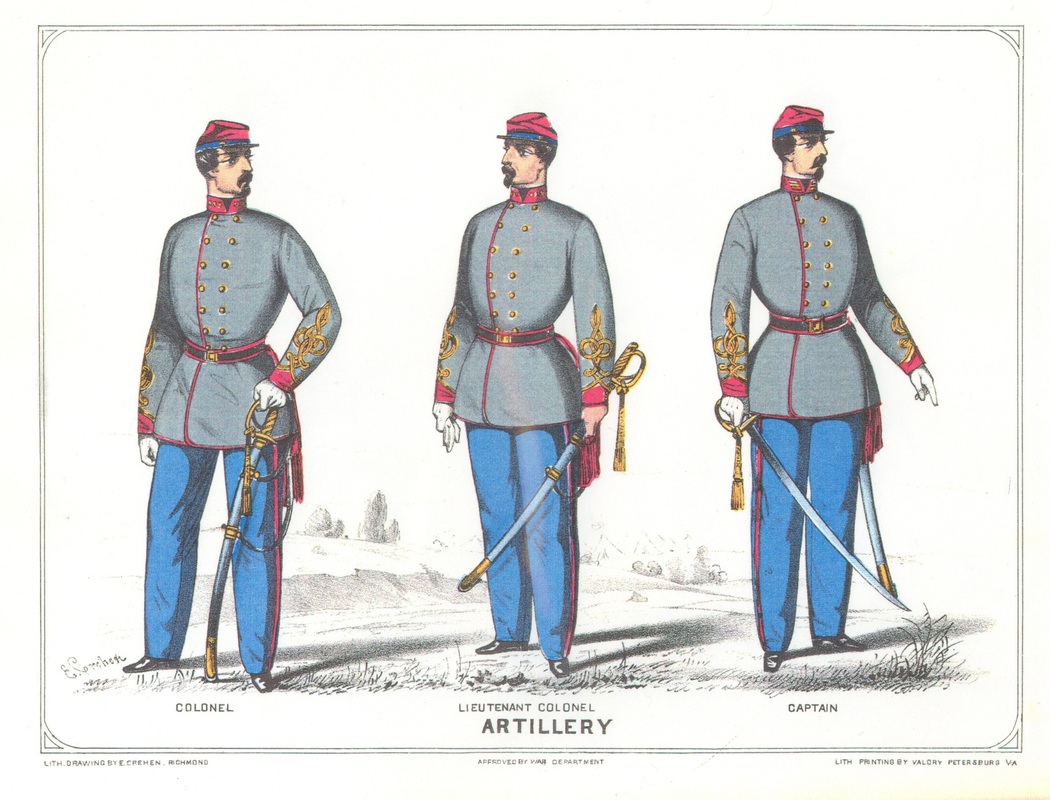

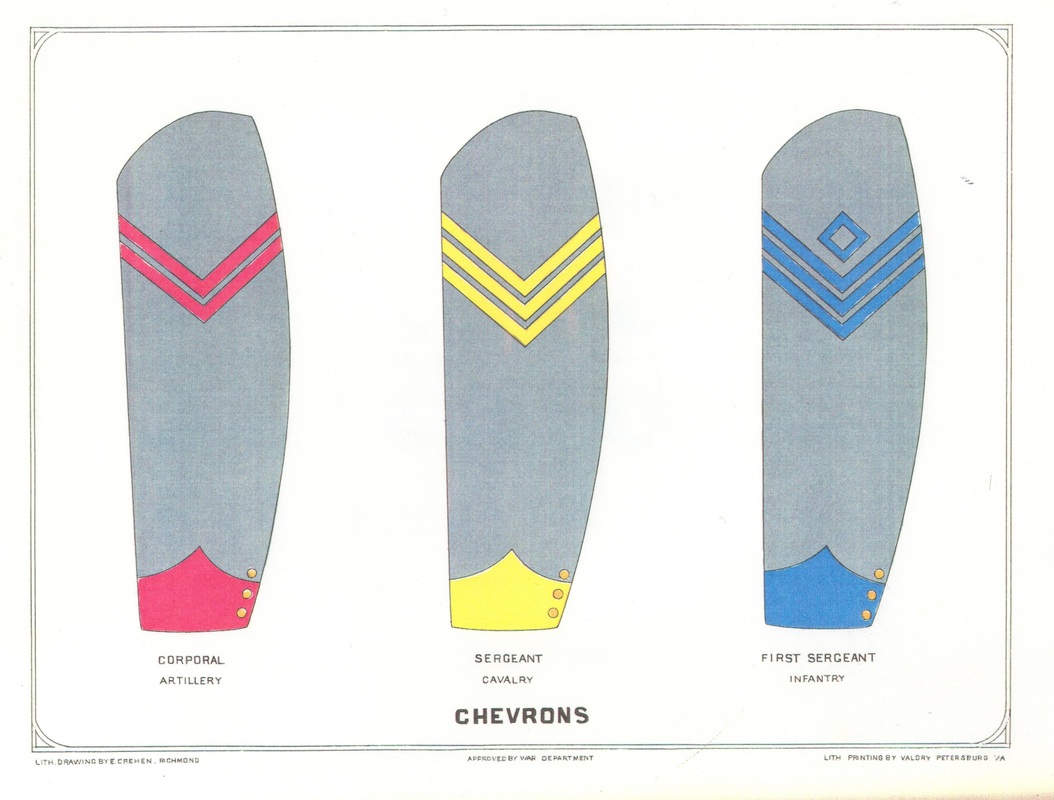

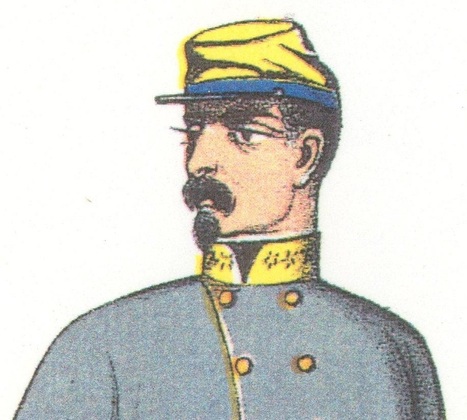

The uniform also had a French lineage. This is reflected in regulation cap, officially described every bit a kepi, merely cut in the chasseur pattern with its hallmark countersunk crown, and low side pieces. Aside from the regulations, contemporaries seldom used the term "kepi," instead calling the regulation headgear a cap. The word "kepi," even so, has gained currency since the war'south cease and become an iconic feature of the Amalgamated uniform. The official double-breasted frock glaze was likewise similar to both the French army frock of the time, and to the Austrian ground forces tunic. This characteristic tin can be attributed to the South's respect for France every bit the preeminent military ability of the day, likewise every bit to the uniform's Prussian designer, Nicola Marschall, who incorporated Austrian characteristics into the Confederate tunic. In fact, Marschall copied both the blueprint and color of the Austrian sharpshooter'due south tunic, it being gray with green-colored facings. British Lieutenant Colonel James Fremantle noted this during his travels through the Confederacy, remarking, "Virtually of the officers were dressed in compatible that is swell and serviceable - a bluish-gray frock coat of a color like to Austrian yagers." The Confederate tunic was to have a relatively short skirt, similar to the French and Austrian tunics, only this stipulation was at odds with the prevailing mode that dictated a knee-length skirt. As such, Confederate frocks near always had long skirts, despite what was prescribed in the regulations. The officer'due south elaborate sleeve and cap braid also followed the French style, as did the that lack of shoulder straps. The officer collar rank closely matched the Austrian rank insignia, while the enlisted chevrons copied the American pattern.

Prototype iv: This painting of French soldiers during the Franco-Prussian State of war reflects the similarities between the French and Confederate uniforms. The kepi and double-breasted frocks, too every bit the officer sleeve and cap complect were models for the Confederate uniform. Prototype in the public domain; Boxing of Bapaume, Full general Faidherbe.

Image 5: A French artillery crew during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 wears the style of frock coat and kepi that the Amalgamated army used as a model for their own uniforms. Image in the public domain.

| Image vi: Confederate General "Prince" John Magruder'south French-made kepi. While Magruder commanded the District of Texas, he is idea to have obtained this kepi, specially made for him in France, and imported through the blockade. Image courtesy of the Museum of the Confederacy. | Image vii: The official Amalgamated uniform regulations of 1861 called for a cap "like in course to that known as the French kepi." The give-and-take "kepi" has ingrained itself into the Confederate lore of today. During the state of war the give-and-take was seldom used: anybody called information technology a "cap." Image courtesy of the Kirk D. Lyons drove. |

| Prototype 8: Virginia militiamen stand up baby-sit at John Brown's execution in December 1859. By this fourth dimension, the French style kepi had become an established American militia cap. The front of the band comes to a indicate on this variant, similar to that of the U.S. M1851 shako. Image courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia. | Image 9: Lloyd Walther Surghnor, Visitor A, 16th Texas Infantry wears the M1861 regulation cap, admitting belatedly in the war. Despite 1862 regulations prescribing night bluish bands and co-operative-of-service color sides and crown, Amalgamated depots continued to brand the simpler M1861 cap throughout the war. The M1861 cap had a co-operative-of-service color band with gray sides and crown. Image courtesy of the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia. |

Paradigm x: The Confederate regulation frock coat was patterned afterward the Austrian army sharpshooter (Jaeger) uniform. This Germanic influence is not surprising, considering that Prussian artist and immigrant, Nicola Marschall designed the Confederate uniform. Image courtesy of the Kirk D. Lyons collection.

| Image 11: Archduke (Erzherzog) Rainer von Österreich wears a typical Austrian, gray-blue tunic with its short skirt, double-breasted forepart, and stars on the collar. The short skirt defied the custom of the mean solar day, and Confederate officers universally ignored the regulation, wearing their frock skirts to the peak of the knee. The Austrian collar rank also formed the basis for Amalgamated officer rank. Paradigm in the public domain; lithograph past Eduard Kaiser, 1860. | Image 12: Nicola Marshall used the Austrian Jaeger tunic every bit the ground for the Confederate frock coat. This epitome is dated 1852. Image in the public domain, artwork from A. Strassgschwandtner. | Image 13: Marschall was especially taken with the Jaeger tunic'southward color scheme: grey with dark-green facings (collar, cuffs, edging). He substituted American branch-of-service colors for Jaeger light-green. Marschall's regulation uniform was too elaborate and expensive to produce, and the quartermaster department simplified the issued compatible to gray jackets and pants. |

2 other American traits influenced the Confederate uniform: the branch-of-service colors, and the lite blue pants. The Confederate regulations specified calorie-free blue every bit the pants colour, probably intending the aforementioned "heaven blueish" shade as the Federal compatible had. This proved troublesome to make, withal, given a lack of resources, so usually pants were fabricated of the aforementioned color cloth as the tunic. Quartermasters did make limited quantities of lite blue pants, however, when they had access to imported lite blue material. The imported light blue textile was dissimilar in colour from the pre-war American sky blue cloth, merely as the imported buck gray was unlike from peacetime buck gray. The Confederates imported a shade called "lite French blueish" that was darker and brighter than the Yankee sky bluish. In any example, some Confederate commanders found the combination of Confederate blue-gray jackets and lite bluish pants too similar to the Yankee uniform, and thus confusing on the battleground, and asked quartermasters to cease procuring the light French blue cloth.

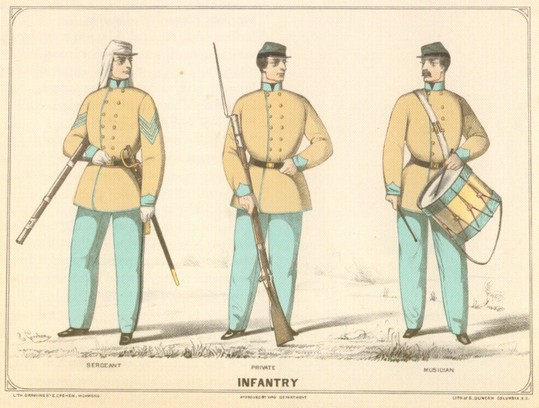

Image 14: Marschall followed American tradition when selecting co-operative-of-service colors: blood-red for arms; yellow for cavalry; and, lite blue for infantry. He also carried over the enlisted chevrons of the "Sometime Army." Paradigm courtesy of the Kirk D. Lyons drove.

| Image 15: The next two images evidence the dissimilarity between Confederate "light French blue" and Federal "sky blue." The Confederates did not try to replicate the Yankee sky blue. Instead, they purchases "light French bluish" from Europe (as depicted in this image). Light French bluish had a darker, bolder and brighter appearance. Cloth swatch courtesy of Charles Childs, County Fabric. | Epitome 16: The Federal heaven blue in this epitome is lighter that the Confederate light blue, with a duller, powder hue. Cloth swatch courtesy of Charles Childs, County Cloth. |

| Image 17: The light French blue trousers of Henry Redwood, tertiary Virginia Local Defence Troops are a Richmond Depot issue. The outside surface is discolored with early twentieth century, coal soot, air pollution, but the within cloth is make clean enough to discern the distinctive color of Confederate import, light blueish. Artifact courtesy of the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia. | Image 18: Another view of Henry Redwood's trousers shows a clean surface in a torn seam. The bright blueish shade is similar to what the author's generation chosen "electric bluish" during the 1970s & -80s. Artifact courtesy of the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia. |

| Image xix: Thomas V. Brooke's (3rd Company, Richmond Howitzers) captured Federal chausseur trousers stand for the slow, powder blue color used past the North. Artifact courtesy of the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia. | Image twenty: The contrasting colors of imported Amalgamated blueish cloth are compared here. Francis Goulding's vest on the left (made from a Tait jacket) has the distinctly dark-hued, royal bluish facings. Lieutenant John Satter's frock, on the correct, is faced with light French blue. The author has found royal blue only on Tait uniforms. He has also noted that Confederate low-cal blue trousers and trimmings are commonly made of imported light French blue cloth. Artifact courtesy of Richard Ferry Military Antiques. |

| Image 21: The Confederate uniform regulation intended for light blue trousers. This was problematic considering the Southward relied on imports for light bluish textile, and considering the night blue-greyness jacket material worn with light blue pants resembled the Federal uniform on the battlefield. Paradigm courtesy of the Kirk D. Lyons drove. | Image 22: Pvt. Joseph E. Mayfield, Company H, fourth Texas Cavalry, wears a cadet gray jacket and light blue trousers issued from the Houston Depot on about January one, 1864. Both types of textile were imported into Texas in 1863. Epitome courtesy of Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones 3 collection. |

The elaborate regulation compatible, consisting of a cadet gray, double-breasted tunic; calorie-free blue pants; and, colorful kepis was problematic from the start. The South did not have the broad array of colored textile to make such complex uniforms, nor were quartermasters inclined to squander resources making double-breasted tunics. In fact, the Confederate Quartermaster General published a revised fix of uniforms regulations a calendar month before the official Confederate uniform regulations appeared that prescribed a vastly simplified uniform. The double-breasted enlisted tunic (that called for fourteen large buttons and four pocket-size gage buttons) was replaced past a single-breasted jacket that required just 7 big buttons and less than two-thirds the amount of cloth. The cadet greyness, light bluish and various trim colors (reddish, yellow, light blueish and dark blue) were also superceded past a single basic uniform color of gray. The clothing agency settled on a loosely-defined jacket pattern that allowed for local improvisation based upon what materials a local quartermaster might have had available. In this regards, American practicality influenced the uniform that actually prevailed over the regulations: a brusk jacket and pants of a matching color in "grey…or whatever colour [available]," and sparing of materials. The compatible was also topped off with the utilitarian, soft, wool felt slouch hat, some other American influence that would symbolize the Confederate uniform both in fact and in lore.

The American-inspired co-operative-of-service colors of light bluish for infantry, cherry-red for artillery and yellow for cavalry were far from universally employed. The colored trim cloth proved expensive, difficult to obtain, added to production fourth dimension and costs, and impeded a universal issue to all branches. For these reasons, many depots opted for a plain, universal uniform, devoid of branch color. Still, some depots did add together branch trim to their uniforms, and throughout the war, uniforms from diverse sources included co-operative colors. Past far, red artillery trim predominated in its utilise. Calorie-free blue was used to a far lesser degree and yellow trim was rarely used on the Amalgamated uniform. This was due in no pocket-size part to the fact that blood-red material or braid was easier to obtain than lite blue or yellowish trimmings. Dark blue trim by and large supplanted light blue, since information technology, too, was easier to come by that light bluish trim, and night blue was frequently used on infantry uniforms early in the war, and later depot jackets in the Lower Southward. Perhaps the most widespread trim color to be used, peculiarly early in the war, was black. This color of cloth was easy to obtain since it was the prevailing men'due south clothing colour. As such, black not only became the default, substitute infantry trim color, it was often used past the cavalry, as well. Indeed, black became a sort of universal trim color used by all branches throughout the war.

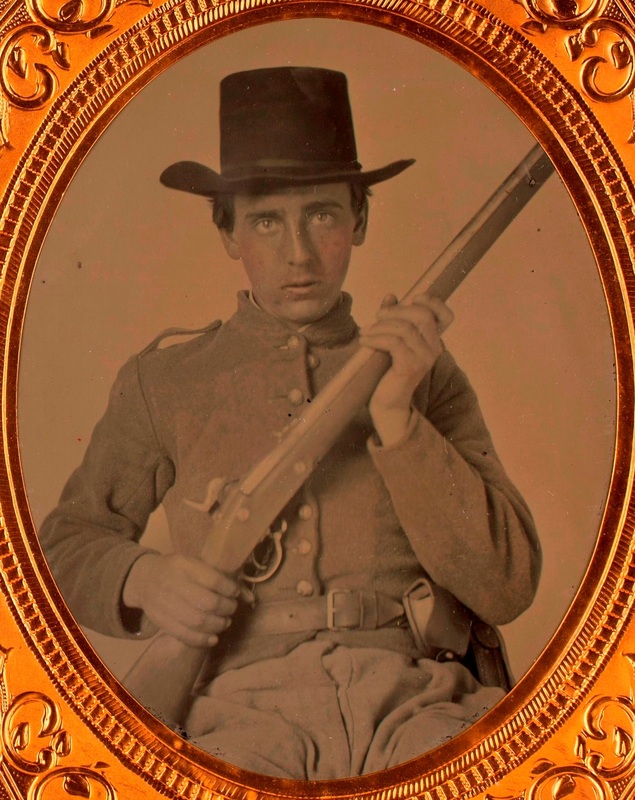

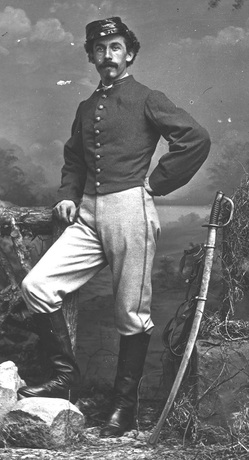

While the enlisted, double-breasted tunic was never universally adopted, the single-breasted, enlisted frock glaze was the most widely worn "mustering-in" garment for the outset twelvemonth or then of the war. Few were fabricated the quartermaster section, merely companies going off to war had them them made locally by contractors, tailors or volunteer aid societies. While this garment is nowhere to be found in any Amalgamated regulation, it was, by 1861, America's unofficial militia uniform. It institute its inspiration in the Pattern 1851, and 1859 US Ground forces uniforms. Southerners peculiarly copied the 1851 pattern frock coat with distinctive collar and cuff facings in the co-operative-of-service color. The cuff was fashioned with an upward point on the outside. This Confederate version of the pattern 1851 frock coat became universally copied from Texas to Virginia, using cadet gray, steel grayness or butternut brown in lieu of dark blue for the basic textile, and substituting the easily obtainable black for the usual co-operative color facings.

| This color plate of the the US Army dragoon uniform shows the master features adopted by Southerners for their own enlisted, unmarried-breasted frock coats, especially the collar and cuff facings. Confederate frocks typically had an eight- or nine-button forepart, but the skirt was longer, reflecting the electric current way of 1861. | In this movie, Joseph Newman Rock wears his initial, mustering-in uniform. This uniform includes the Confederate version of the design 1851, single-breasted apron coat with black facings. Epitome is courtesy of the Sam Higginbotham collection. |

| Epitome 23: The following three images draw Richmond Depot jackets in the typical colors used by the Confederate quartermaster. This jacket in the regulation buck grey (imported, dark blue-greyness kersey), without facings, matched the quartermaster regulations perfectly. Artifact courtesy of the Gettysburg National Military Park. | Prototype 24: This tailor-fabricated Richmond await-alike jacket is made of steel grayness (medium gray) satinet. Steel gray was one of the chief colors that domestic dyers tried to reach for Confederate fabrics. Artifact courtesy of the Atlanta History Eye, Wray collection, Atlanta, Georgia. |

Image 25: Abraham Adler, Company E, 21st Mississippi Infantry, wore this Richmond jacket at the battle of Chickamauga. Although it has faded to tan from a greyness color, its butternut shade would accept been adequate uniform color to Confederate quartermasters. Artifact courtesy of the Louisiana Country Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana.

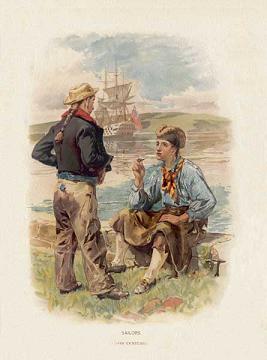

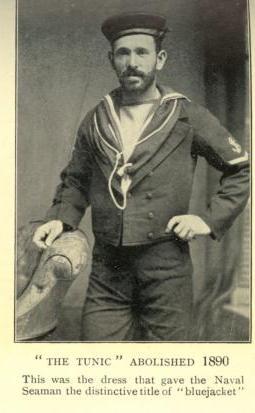

The Amalgamated jacket was often referred to as a "shell" jacket, a term with nautical roots. The shell jacket was the universal sailor'south garb, and the proper name comes from the British term "shell back," which was a nickname for British sailors. The other term used for the Amalgamated jacket, "roundabout," referred to the fatigue jackets made in the early nineteenth century, cut all the fashion effectually the waist, instead of being made with tails as coatees were. Confederate jacket patterns conformed only in the broadest sense: they had standing collars and wide sleeves. Many of the surviving jackets are besides of a distinct color, known today as butternut, which go a Confederate icon.

| Image 26: The quintessential Confederate jacket's nickname, "vanquish jacket," traces its roots to the British sailor's nickname "trounce back," which by extension came to define the crewman'south classic jacket. Image courtesy of www.wheathamstead.net. | Epitome 27: This gimmicky image shows the back of an English sailor'due south jacket. Image courtesy of www.St.-George-Squadron.com. | Epitome 28: This epitome captures for posterity the classic, British sailor "bluejacket" as information technology was existence phased out of service. Image courtesy of www.godfreydykes.info, Royal Navy Boys Pay and Kit Issues, 1815-1919. |

| Prototype 29: The other common nickname for the Confederate jacket was "roundabout." This term stemmed from the early nineteenth century fatigue jacket that was issued in lieu of the tail coat, being cutting "round-nigh" instead of with tails. Ironically, these early fatigue roundabouts were gray, just every bit the Amalgamated jackets would be during the Civil State of war. Paradigm courtesy of Don Troiani, Historic Art Prints. | Image thirty: The butternut jacket of William A. Branch, Company G, 57th North Carolina Infantry, embodies the typical Confederate shell jacket or roundabout in color and cutting. Antiquity and image courtesy of Northward Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh, Northward Carolina. |

The butternut icon deserves some explanation. When people think of butternut today, they are apt to draw it as a low-cal, yellow-brown. The origins of the term butternut are more complex, because information technology originally encompassed a color, a blazon of homespun cloth, and a people. The term originated in North. As numerous Southerners moved to southern Illinois and southern Indiana in the mid-nineteenth century, the native Northerners called them "butternuts" for the butternut-dyed, rough homespun cloth they wore. Later on, during the Civil State of war, the they called Confederate soldiers "butternuts" using the same criteria: Southerners wearing rough-textured cloth of the feature light chocolate-brown color. The nickname applied regardless of whether the colour had originally been brown from walnut hull dye, or had been dyed gray at the mill and faded to brown. Equally then, it would have been applicable to bootleg citizens garb, or to factory fabricated uniforms, as long as the material's texture resembled "homespun." Southern-made cassinets, jeans and satinets might all have resembled homespun to a Northerner.

When considering butternut as a color, which the term eventually morphed into by the end of the war, it was a light tan to a light chocolate-brown color, depending on how the fabric had been dyed. The original butternut color was derived from Northern home dying using walnut hulls of the white walnut tree, commonly known also as the butternut tree. The white walnut, or butternut tree's botanical name is Juglans cinerea , and its range includes eastern North America from Canada, southwards to northern Alabama , and westwards to Minnesota and northern Arkansas . Information technology is absent from most of the Southland . Northerners used butternut bawl and nut rinds (hulls) to dye textile to colors between light yellow and dark brown. The more than concentrated the dye, the darker the resulting color. None used butternut dye used commercially; they used it exclusively for homespun cloth (hence its association with homespun). This white walnut, butternut dye rendered fabrics a light to medium, yellowish brown color.

Likewise, the eastern black walnut, Juglans nigra , was more prevalent in the South. It is native to eastern North America , ranging from southern Ontario , westwards to southeast Southward Dakota , southwards to northern Florida and westwards from the due east declension to primal Texas . Southerners commonly used the black walnut tree, or "butternut" by extension, to dye their homespun vesture at the time of the Civil War. The b lack walnut drupes (hulls) comprise juglone , and produce brownish-black dye. The tannins nowadays in walnut hulls deed equally a mordant , aiding in the dyeing process, and making the resulting color extremely resistant to fading. Despite the black walnut dye's potential to yield a night, brownish-black color, rural folk mostly obtained from it a light to medium, warm brownish color for their homespun fabrics. Homemade, citizen clothes that were sent to Confederate soldiers from their families take this distinctive colorfast, warm, lite brown shade.

| Paradigm 31: The homemade clothes of Burton Marchbanks, 30th Texas Cavalry, reverberate the warm, medium-low-cal brownish shade rendered when walnut hulls were used to home-dye fabrics and yarns. Artifact courtesy of the Layland Museum of History, Cleburne, Texas. | Epitome 32: The light tan colour of Francis M. Freeman's Richmond jacket is typical of that encountered in domestically-dyed, Southern factory cloth. The jacket appears to take been low-cal grayness (remaining nap color), but faded in the sunlight. Freeman served with the 2nd Battalion, Georgia Infantry. Artifact courtesy of The Cannonball Firm, Macon, Georgia. |

By contrast, factory dyed fabrics, which more often than not ended upwardly as regular army-cut uniforms, had its own distinctive brown shade: a colour ranging from oatmeal to light tan to grayish tan or nighttime tan. This was considering the fabric'south woolen yarn had been dyed with an unstable vegetable dye and mordant, and had faded afterwards exposure to sunlight. Typically, factories used logwood and indigo as dyes, and copperas and blue vitriol every bit mordants. The targeted colors were either "steel" gray (the most common domestically produced shade, being a medium grayness, midway between white and blackness), domestic "cadet" grey (produced much less than steel gray, being a light blue-gray), or light to medium brown (rarely produced). Most such dyed yarns, observed on surviving garments, take faded to a tan or oatmeal color. Some retain traces of the gray nap in protected surface areas, and those that were dyed with specially good mordants retain their steel gray or sometimes brownish gray color. Some even faded to a natural white shade. Chemist and dye specialist Ben Tart of N Carolina has estimated that it took no more than than a month of exposure to outdoor sunlight to fade a domestically dyed steel or cadet grey garment to a tan color.

While discussing the basic colors of Confederate uniforms, i must not forget the terminal ii of these: sheep's grey and natural white. These colors were sometimes referred to as "drab." Numerous surviving uniforms signal widespread usage of these colors in all parts of the Confederacy. Sheep's gray was easy to manufacture because it required no dyestuffs, yet rendered the material a colorfast light gray. Natural white was easier to produce than colored material because its yarns required no dying. The wool still had to be cleaned, however, which added to the fabric'southward comfort by removing excess lanolin. It carried a stigma, however, since white woolens had traditionally been used for slave clothing, and Confederate troops often resented the cloth's association with slaves. As such, the final source of origin for the white Confederate uniforms might exist attributed to the American slave culture, every bit well equally the time-honored practice of American practicality trumping all other considerations.

| Paradigm 33: Bluford Watson Adams's satinet jacket represents the undyed "sheep's gray" shade. Adams served with the 2d & fourth Kentucky Cavalry Regiment. Artifact courtesy of the Civil War Museum of the Western Theater, Bardstown, Kentucky. | Paradigm 34: A Spousal relationship cavalryman took this natural white woolen jacket as a souvenir from a captured Amalgamated clothing warehouse in Dublin, Virginia. Information technology is typical of the white uniforms used by all Amalgamated armies throughout the South. Image courtesy of the Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, Georgia. |

A final remark is appropriate regarding Amalgamated uniform colors: butternut preceded the use of cadet gray by far. Many take the misguided notion that the loftier quality, imported British kersey, in cadet "grey" (as the British spelled it), was an early state of war product, and that as the S was blockaded, its quartermasters were reduced to using inferior "homespun" jeans, dyed with butternut juice. This thought is incorrect. The fact is that domestic fabrics that had been dyed domestically predominated early on in the state of war. Every bit foreign contracts came into play, cadet gray and light bluish kerseys increasingly replaced these domestic fabrics in many Confederate armies. As the Confederate industrial base developed towards the end of the war, domestic fabrics were making stiff "come-back." By early on 1865, however, the average Confederate soldier in the Army of Northern Virginia, the Mobile Garrison or the Trans-Mississippi was more likely to take been clad in imported, cadet greyness kersey than in domestic, butternut jeans.

Having touched upon the origins of the Amalgamated uniform and its basic colors, some explanation of quartermaster vesture production and issue is necessary.

The first uniforms were furnished past several sources: local volunteer groups, small private contracts, and Confederate and state quartermasters. Because few believed the war would last very long, and the regime did not desire to invest public funds in permanent clothing factories, a system of compensation was developed for soldiers and regimental commanders who furnished theirr own clothing or bought clothing for their control. This stop-gap measure was known as the " commutation arrangement." It was officially abolished in Baronial of 1861, but due to inadequate production on the function of the quartermaster department, commutation lingered until October 1862. Quartermasters relied heavily upon individual contractors to manufacture wearable at considerable short-term expense that avoided a long-term investment. Past the middle of 1862, the quartermaster department had adult its own factories to a considerable extent, and Southerners were no longer averse to sponsoring such expenditures. They had come up to realize that the war would concluding for a long fourth dimension, and that the government needed to presume full responsibility for clothing the troops, along with establishing regular, government manufacturing facilities and fully operational clothing bureaus. As the war dragged on, the government weaned itself off of domestic contracting, to a large degree, by edifice its ain factories, and supplemented its own product with foreign bought finished goods. By the finish of the state of war, the South had a well-functioning manufacturing base of operations, a reliable supply of foreign imported materiel, and domestic contracts that made upward for the shortfalls in production that the onetime sources could not fulfill.

Paradigm 35 (showing forepart and rear): Charles Herbst, Company I, 2nd Kentucky Infantry, wore a single-breasted, butternut frock coat typical of early on war Confederate enlisted uniforms. The long skirts used too much fabric, however, which compelled quartermasters to prefer resource-conserving jackets. Artifact and image courtesy of the Mike Cunningham drove.

| Epitome 36: A Federal soldier recovered this early war-fashion, single-breasted frock glaze from the abandoned Confederate trenchline in Trivial Rock, September 1863. Many of these frocks had collar and cuff facings. Artifact courtesy of the Steve Osman collection. | Image 37: The Arkansas frock coat offers an example of successful dying with a resilient mordant, one that retained the yarn's bold, steel gray color. Antiquity courtesy of the Steve Osman collection. |

This was a gradual process, even so, with overlap throughout the war in how the various methods of habiliment procurement was accomplished. To kickoff with, both the Amalgamated and the various land governments stepped in to mass produce clothing long before the Confederate government officially ended the commutation organisation in Oct 1862. In fact, by that time, numerous government "depots" had come into existence and were in full production throughout the South, even though many used contractors as their source of supply instead of authorities-owned shops. To start with, the states took the initiative to manufacture clothing for their own troops serving in the Confederate army. Many of u.s. produced wearable from the very beginning to the terminate of the war. North Carolina is the best known among uniformologists, having produced vast quantities of uniforms and imported more than besides. Less well known, however, were the clothing bureaus of Tennessee, Alabama, South Carolina and Georgia. Prior to its fall to the enemy, Tennessee supplied the needs of the Confederate army in the state. Alabama produced prodigious quantities of wear for Alabama troops, and the other two same states provided minor quantities of clothing to their ain soldiers. The State of Arkansas established a very successful clothing agency that provided for troops until the Amalgamated authorities were able to take responsibility for quartermaster functions. Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi established modest habiliment operations for their troops, every bit well. The important fact to keep in mind is that well-nigh of these country operations had been in operation from the offset of the war, and all were performance long before the Confederate quartermaster clothing bureaus started functioning.

Paradigm 38: Amzi Leroy Williamson, Company B, 53rd North Carolina Infantry, wore this North Carolina jacket and cap. The Land of North Carolina dyed its uniform fabrics either steel gray or cadet grey. In all likelihood, the present butternut color is a effect of fading. Antiquity and image courtesy of the Nib Ivey collection.

| Image 39: John Immature Gilmore, 3rd Alabama Infantry, wore this Alabama State jacket. Note the plumb collar, as per state regulations. Artifact courtesy of the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia. | Image xl: Archibald Smith's jacket conforms with other jackets thought to be Georgia Land uniforms. Smith served with the Georgia War machine Institute Corps of Cadets confronting Sherman'southward army. Artifact courtesy of Atlanta History Eye, Atlanta, Georgia. |

The Confederate clothing bureaus began somewhat haphazardly. They began equally demand arose and at that place was no 1 at that place to see information technology. The Regular army of Mississippi managed organize a organisation of supply for its troops by the Battle of Shiloh. The San Antonio and Houston quartermasters opened authorities shops early in 1862, and had fully functioning operations past the fourth dimension commutation officially ended. Judging from the plethora of images of Army of Northern Virginia troops wearing Richmond Depot jackets and caps early in the war, information technology would announced that the Confederate quartermaster in Richmond as well had a well-functioning clothing agency long before October 1862. Other Confederate quartermasters operated similar manufactories.

| Epitome 41:, Northward Carolinian E.C.N. Green wore this tailor-fabricated, early on version, Richmond Depot jacket, complete with shoulder straps and colored facing tape. The calorie-free shade, cadet grayness cloth is probably "Crenshaw's gray" from the woolen manufactory of the same proper name. Another early on depot-made jacket is fabricated from the same cloth, but without facing tape. Artifact and image courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh, Due north Carolina. | Image 42: Elijah Crow Woodward'south Columbus-Atlanta jacket is another example of an early Confederate depot uniform that pre-dates the end of substitution. Woodward served with Company C, ninth Kentucky Infantry. Artifact courtesy of the Kentucky Military machine History Museum, Frankfort, Kentucky. |

The starting time authorities depots were relatively small or dispersed. Those of Mississippi reflect this well. During the early on part of the state of war, the Confederate vesture bureau at that place relied on the production of several small factories to replenish the soldier suits that information technology issued. Each individual contractor, or factory, produced a limited, simply steady quantity of uniforms each week. The aggregate production of several small factories sufficed to run into the demand of the army in that area. For instance, on March 21, 1863, the Daily Southern Crisis newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi reported that five Mississippi factories, in Bankston, Columbus, Enterprise, Natchez and Woodville, together produced 5,000 garments weekly. Furthermore, each mill may have used its own patterns, which meant that there were subtle differences in the soldier suits produced at factory. This do was fostered by the overall leniency in Confederate compatible specifications. As long equally a manufacturer made jackets with continuing collars, for instance, he was allowed considerable latitude for the residuum of the design. The sleeves might be one- or ii-piece; the jacket might have anywhere between v and nine buttons; information technology might have had an inside or an outside pockets; it might take had trim or been plain; it might accept been fabricated from cassinet, jeans or satinet; and, it might take been natural white, sheep'due south gray or steel gray. Considering the large number of pocket-sized factories, the varying durations of their operations, and probability that each mill inverse its patterns and materials always and then oftentimes, the variety of jackets emerging from the Confederate quartermaster bureau must take seemed endless.

Applying this aforementioned model described by the Daily Southern Crisis, the quartermaster in Jackson would receive five types of jackets, in varying proportions, that he issued out indiscriminately, i.due east. with little regard to whatever typology equally we uniformologists view it today. In 1863, a jacket was only a jacket regardless, and when a brigade quartermaster received 2,000 suits of jackets and pants in Mississippi, they included whatever was in the depot store house on the day he picked upward his wearable. The 2,000 suits might have been the products of five different factories, and all of the jackets may accept varied slightly. The following array of "Deep S" manufactory jackets illustrates this variety in construction and materials, yet all are plain shell jackets with standing collars.

| 43. John T. Appler, Co H, 1st & Co K 4th Missouri Infantry Regiments wore this jacket with a similar pair of pants. The suit was probably made and issued in Mississippi in mid-1863 (based on Appler'south service). The jacket has a 9-button front end (Federal, general service buttons); four-piece body (no side pieces); jumpsuit sleeves; jumpsuit collar (inside and out); and, one outside left breast pocket. The bones cloth is a two-over-one cassinet; natural white, undyed woolen weft; low-cal brown cotton warp; and, unbleached osnaburg lining. Artifact courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, Saint Louis, Missouri. |

| 44. This jacket was worn by an unidentified soldier, and based solely on its similarities in materials and construction to other identified jackets, it was presumably made and issued in Mississippi in 1862 or 1863. It has a six-button front end (cast brass, Roman I buttons); four-piece body (no side pieces); one-slice sleeves; and, no original pockets. The bones cloth is a patently weave, woolen-cotton wool cloth; undyed woolen weft and brown-stained cotton warp; and, an unbleached osnaburg lining. Artifact courtesy of the Smithsonian Establishment, Washington, DC. |

45. John B.L. Grizzard, of Hanleiter'southward Company, Georgia Light Artillery, wore this white jacket. It was probably made and issued in Georgia, given the factor of proximity, since Grizzard joined the regular army in Feb 1864 in Atlanta, and probably received clothing there before long afterwards. The basic fabric is a 2-over-one, woolen-cotton jeans; natural white woolen weft; natural white cotton fiber warp; unbleached osnaburg lining in the body; and, polished cotton inside the sleeves. Information technology has a 5-push button front (brass dome buttons); vi-slice torso; ii-slice sleeves; two-slice neckband (inside and out); and, ane outside left chest pocket. Artifact courtesy of the Texas Civil War Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

46. An artillery jacket from an unidentified soldier besides appears to exist a Lower Southward product. Based on the fact that it has survived, and that it does not conform to afterwards depot variants that introduced more stringent pattern guidelines, the jacket may have been made and issued in the Lower Southward in 1863 or 1864. Information technology was presumably owned past a Mississippi soldier, based on its being role of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History collection. The basic cloth is a two-over-one jeans; sheep's gray woolen weft; natural white cotton warp; and, unbleached osnaburg lining. It has a six-push button front (Federal, eagle C buttons); six-piece trunk; two-piece sleeves; two-piece collar (within and out); ii within breast pockets; and, ruby-red woolen edging at the base of the cuffs, around the border and base of the collar, and along the unabridged edge of the jacket. Artifact courtesy of the Mississippi Section of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi.

47. Corporal J.C. Zehring's jacket typlifies the diversity of uniforms made in small factories until the very end of the war. Zehring, detailed from the 4th Tennessee Infantry, served as a hospital steward in Milledgeville, Georgia during the latter part of the war. His jacket may have been made and issued in Milledgeville in early 1865. The jacket cloth is brownish-tan, satinet or jeans; a woolen-cotton textile, with a lite brownish woolen weft, and a natural white cotton warp; and, an unbleached osnaburg lining. Information technology has a six-push front (Federal staff officer buttons); 6-piece body; 1-piece sleeves; and, two-piece collar. Antiquity and paradigm courtesy of Equus caballus Soldier Military Antiques.

Confederate uniformologists take come up to acquaintance specific jacket characteristics with certain depots, only this ignores many bodily circumstances. For case, depots seldom concerned themselves with following stringent patterns: the broad criteria of furnishing curt jackets with continuing collars more often than not sufficed. These relaxed standards as well fostered ease of production, also, especially because that shortages of materials oftentimes led to improvisation. Uniformologists should also bear in mind that Confederate jackets were not sacred garments, they were clothing: cipher more, and nothing less. Few would have idea much well-nigh the different number of buttons on their authorities-furnished jackets in 1863.

That said, Confederate quartermasters did attain a fair degree of uniformity in their patterns equally the war progressed, at least inside their own depot-sphere. Some depots managed to produce well-divers patterns that remained abiding from early in the war to the terminate. The jackets from the Richmond, Virginia and Columbus, Georgia Depots are the all-time examples. The nine-push Richmond jacket, with shoulder straps, belt loops and two piece sleeves, may take been made as early on as 1861. The gray jeans Columbus jacket with 1-piece sleeves and night blue facings on the low cut neckband and straight cuff facings was produced at least from the fall of 1862 until the end of the war. Other clearly definable jackets might not have been first produced until 1864. Such may have been the case with two depot jackets from the Section of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. The start was probably made by the Columbus, Mississippi Depot. It was a five-button, satinet jacket, with ii-piece sleeves, exterior breast pocket, and dark bluish facing on the collar only. In order not to confuse it with the Columbus-Atlanta Depot compatible, I phone call it the Anderson jacket after Major Anderson who was in accuse of that depot. The other had seven wooden buttons, a satinet body, one-piece sleeves, and exterior, left breast pockets, and often, a double row of elevation stitching around the border. This second jacket was probably made by the Selma and Montgomery, Alabama operation, which I refer to as the Montgomery jacket. Past the terminate of the war, it was indeed possible to notice conspicuously definable characteristics in the various depot jackets and assign them typologies (every bit Les Jensen did). Up until the last part of the war, however, this degree of uniformity did not necessarily exist within many depot operations. Even depots that had well-established compatible jacket patterns from early in the war still issued variants. The Richmond Depot issued limited quantities of four-button sack coats, and a 5-button jacket variant from a factory in Southwest Virginia to supplement its product of the quintessential nine-button Richmond jacket. Even the Richmond jacket was sometimes made with six, seven or eight buttons instead of nine. Modest Georgia factories produced a wide range of unproblematic jackets throughout the state of war that supplemented the production of the well-defined Columbus jacket.

| Image 48: John Cocke Ashton'south jacket exemplifies one of the virtually iconic Amalgamated uniforms of the state of war: that of the Richmond Depot. Information technology was the uniform of Robert E. Lee'south Army of Northern Virginia. Ashton'due south jacket was made after the characteristic features had been well established, simply is nonetheless typical of the early war production, being made with arms edging and of jeans material. The jacket was issued to him later on his enlistment on July 29, 1864 with the Norfolk Light Artillery Dejection, a Virginia bombardment. Antiquity and image courtesy of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Museum, Virginia. | Epitome 49: This cadet grayness Richmond Depot jacket, picked upwardly at the Battle of the Wilderness by a soldier in the fifth Maine Infantry is typical of a late war variant with shoulder straps and Amalgamated-upshot wooden buttons. By the time the Richmond Depot made this jacket, it had standardized with a nine-push button front, two-piece sleeves, vi-slice body, and, generally made of imported, buck gray kersey. Artifact and prototype courtesy of the Fifth Maine Museum, Peak'southward Island, Maine. |

| Prototype 50: Private David Fenimore Cooper Weller, Visitor C, second Kentucky Infantry, wore this Columbus-Atlanta, Georgia Depot jacket. The Columbus jacket is peradventure the 2d all-time known Confederate depot compatible, and may have been the about prolific, second only to the Richmond compatible. This jacket was made and issued after its salient features had been established, to include its six-push front, facings on the collar and cuffs (the latter cut direct across), jumpsuit sleeves, six-piece trunk, and a rough, jeans cloth body. Artifact courtesy of the Kentucky Armed services History Museum, Frankfort, Kentucky. | Image 51: The Columbus, Mississippi Depot made prodigious quantities of a distinctive jacket, commonly identifiable by its night blue, woolen jeans collar, its five-button forepart (more often than not wooden quartermaster buttons), its butternut-colored jeans fabric, and an outside breast pocket. Andrew Jackson Duncan, 11th Mississippi Cavalry, wore this jacket, that incorporates all of the salient features. The jacket also included two-piece sleeves, and a six-piece body. Artifact courtesy of the Alan Hoeweller drove. |

Image 52: Montgomery and Selma Depot had standardized another identifiable blazon of jacket past the latter part of the war with a considerable production. This "Montgomery" jacket is recognizable past its seven-push button forepart (generally wooden quartermaster buttons), its sheep's gray or butternut-colored jeans textile, its double-row of stitching forth the exterior edge, and an outside chest pocket. An unknown Confederate soldier wore this Montgomery jacket that'south salient features include jumpsuit sleeves, and a six-piece body. Antiquity courtesy of the Gettysburg National Military Park, Pennsylvania.

Image 53: The Augusta Depot produced an all woolen, plain-weave jacket, hands recognizable by its plumb collar on the left side and a six-button front end (generally wooden quartermaster buttons). The plain weave consists of an undyed, natural white woolen warp and a dark, bluish grey woolen weft, which gives the result of a medium-dark, steel gray colour from ten feet away. Start Sergeant J. Fullerton Lyon, 19th South Carolina Infantry wore this Atlanta jacket. Its other salient features include i-piece sleeves, and a half-dozen-piece body. Artifact courtesy of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room, Columbia, South Carolina.

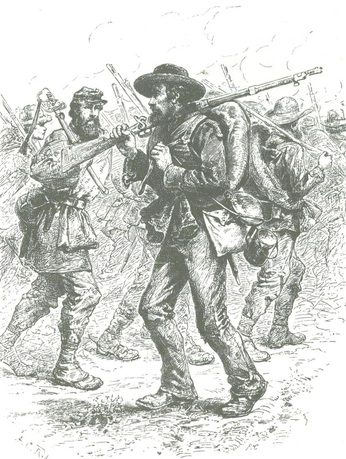

Despite varying degrees of uniformity in jacket patterns, the overall popular image of the Amalgamated soldier remains very distinct: a lean soldier with either a slouch hat, with its brim pushed upwardly in front end, or a French manner "kepi" cap; a gray or butternut beat out jacket; a bedroll slung over his left shoulder and resting at his right hip; and, his socks pulled over the cuffs of his pants. In this guise, his statue withal stands guard over many public squares throughout Dixie, watching over his honey Southland forevermore.

| Image 54: An unidentified Amalgamated artillery lieutenant, believed to be from the Mobile garrison, poses defiantly for a photograph in New Orleans, ca. May 1865. His jaunty cap set askew and his curt, tight fitting shell jacket mark him as a true "Johnny Reb." Image courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia. | Epitome 55: Amalgamated veteran and artist, Allen C Redwood captures the essence of the Confederate infantryman this sketch. Slouch hats, trounce jackets and bedrolls are in testify, and the officer wears the classic "kepi" cap. Image courtesy of Battles and Leaders of the Civil State of war, Volume 2, Part 2, page 515. | Paradigm 56: Dynamichrome has brought one of the most iconic images of the Confederate soldier to life in this colored prototype of the center Amalgamated prisoner at Gettysburg. A lean soldier with a slouch hat and a bedroll, wearing a butternut uniform, he embodies the expect of the Confederate enlisted human. Paradigm courtesy of Dynamichrome and the Library of Congress. |

Epitome 57: One hundred and l years afterwards the state of war, and Johnny Reb nonetheless keeps a vigilant picket over Dixie. Epitome of the Confederate monument , Leesburg, Virginia; public domain.

The author extends his gratitude to all of the institutions and individual individuals who made the images in this article available (as credited in the captions). R eaders are reminded that the images herein are the holding of Adolphus Confederate Uniforms, except where noted as being in the public domain, Library of Congress, or the U.South. Regular army. Fifty-fifty if an artifact or image is credited to a public institution, the paradigm itself is the holding of this website, having been made past, purchased by or given usage of to the writer. Please practise not reproduce these images without the obtaining the writer's consent.

Source: https://adolphusconfederateuniforms.com/basics-of-confederate-uniforms.html

0 Response to "what did n.c. contributer to the confederate army"

Enviar um comentário