Describe the Freudian Revolution and Its Impact on the Arts

Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis and Civilisation and its Discontents belong to two distinct phases of Freud's thought—a thought which was always irresolute, expanding, and beingness revised , and which has every bit many discontinuities equally continuities. Both texts residual written from Freud'southward basic psychoanalytic perspective; each reflects the full general historical, philosophical, and scientific movements in which Freud found himself when he developed psychoanalysis.

Freud's Republic of austria of the second one-half of the nineteenth century was characterized by an fifty-fifty more rigorous form of Victorian sexual morality than England, whose sexual delicacy and frigidity is often caricatured. This rigorous sexual morality did not, withal, prevent Victorians from speaking about sexuality.

Gustav Klimt's Danae, 1907. (Wikimedia Eatables) Klimt's work captures visually many themes that preoccupied Freud in turn-of-the-century Vienna. The large, urban, professional middle class—the bourgeoisie—had an intense moral preoccupation with sexuality, particularly in women and children. Their sexual interests, and sexual knowledge, were understood to be naturally limited; however, in the case of exceptions, this interest and noesis were carefully regulated. Immature women were expected to be celibate before matrimony; and the private sexual experimentation of children and adolescents—for example, masturbation—were assiduously suppressed. Additionally, a growing knowledge of sexual diseases, like syphilis, created, in the public mind, an association between sexual promiscuity and catastrophic epidemics. Sexuality non just needed to exist regulated past personal morality, or by the vigilance of the family unit, just, since information technology could bear upon entire populations, was a political and social business organisation.

Gustav Klimt's Danae, 1907. (Wikimedia Eatables) Klimt's work captures visually many themes that preoccupied Freud in turn-of-the-century Vienna. The large, urban, professional middle class—the bourgeoisie—had an intense moral preoccupation with sexuality, particularly in women and children. Their sexual interests, and sexual knowledge, were understood to be naturally limited; however, in the case of exceptions, this interest and noesis were carefully regulated. Immature women were expected to be celibate before matrimony; and the private sexual experimentation of children and adolescents—for example, masturbation—were assiduously suppressed. Additionally, a growing knowledge of sexual diseases, like syphilis, created, in the public mind, an association between sexual promiscuity and catastrophic epidemics. Sexuality non just needed to exist regulated past personal morality, or by the vigilance of the family unit, just, since information technology could bear upon entire populations, was a political and social business organisation.

At the same time the nascent field of sexology was developing. A number of medical researchers, like Havelock Ellis and Richard von Krafft-Ebing—whom Feud knew and who publicly commented on one of Freud'southward earliest papers—gave detailed and meticulous accounts of the forms and varieties of sexual behaviors and identities, regardless of their rarity or credible perversity. They as well tried to connect facts about sexuality to other facts, which had no cocky-evident human relationship to sexuality; they asked, for example, how sexuality relates to form, or how sexuality relates to criminality.

The late nineteenth century was, therefore, characterized past an interesting constellation of trends: a personal, familial, and political regulation of sexuality, on the one hand, and a proliferation of scientific writing which showed how that problematic sexuality still had a secure and all-encompassing place in man nature, on the other manus. This constellation served as an cheering context for Freud to develop his theories. Freud described how all kinds of unusual, or "perverse," sexual desires dominate the mind—in children, in neurotic adults, but besides in normal adults. Freud also showed how the heed finds itself in an irrevocable conflict with its ain sexuality: how it fears its sexuality, and tries to avoid and eliminate it, or, most importantly, how it tries to forget information technology, or remove information technology from witting awareness. For Freud, this meant that unusual, "perverse" sexuality had a peculiar fate. Regulated by morality, removed from conscious awareness, but still very much extant, it became "unconscious": no longer under the control of a person'southward self-witting and voluntary choices, it manifested in a person's involuntary actions, like mistakes and slips of the tongues, also as in mental pathologies, like obsession, paranoia, hysteria, and feet.

Freud's psychoanalysis divided the mind betwixt what information technology consciously acknowledges, and what it unconsciously is invested in. This segmentation had philosophical precedents in the nineteenth century. The German Idealists Immanuel Kant and Thou.W.F. Hegel had maintained that the listen has perfectly transparent access to, and complete control over, its ain thoughts, as well equally the actions which those thoughts intend. In response to the Idealists, other philosophers—especially Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche—developed a radically different conception of the mind. According to them, thoughts and deportment are not under a person's conscious and deliberate command. Rather, they arise from a person's will, desires, and torso, of which a person is not witting, and which a person cannot deliberately command. Thought and action derive from a source which is not the "I," but rather an impersonal, wild agency, at the heart of our being merely radically distinct from what nosotros have ourselves to be. Freud's postulation of unconscious thought, and his contention that sufferers of mental pathology think thoughts and perform actions whose source is unconscious, tin can be understood to be an extension of this movement against German language Idealism.

The idea that thought and action could accept its source in something other than the "I"—in something wild and unknown to us—was also influenced by a theory which Freud vehemently affirmed and rigorously applied, and which nearly every innovative thinker in the nineteenth century adopted for their ain purposes: Darwin's theory of evolution. A major claim of Darwin's theory of development is that the biological structures that govern the life of gimmicky organisms take their source in biological structures which govern the life of organisms that existed in the archaic past. In the case of homo beings, this suggests that the biological structures found in primitive humans, living thousands of years ago, are all the same operative in contemporary human beings. Many of Freud'southward theories can exist understood to exist an expansion of this idea. The sexual desires which are manifested in mental pathologies, and which go along to exercise effects even in the well-nigh civilized human beings, practise non derive from a person's present interests, preoccupations, and decisions. Rather, they are inheritances from the primitive history of the human species, and a history over which, clearly, a person exercises no conscious command. Additionally for Freud, and at a much more local level, an adult's sexual desires tin can also be understood to be an inheritance from his or her personal primitive by—from his or her babyhood sexual desires, over which, once again, he or she does not exercise any conscious command.

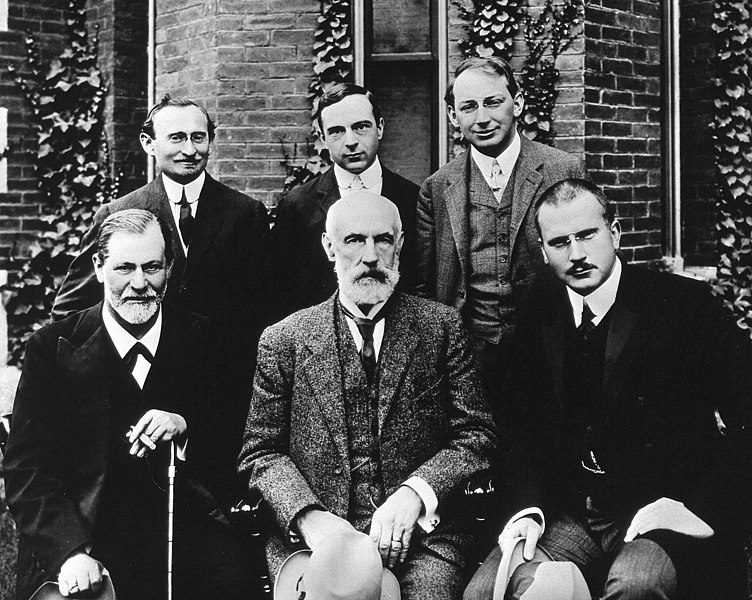

Freud on his visit to Clark University in the United states, 1909. Front, from left to right: Sigmund Freud, G. Stanley Hall, C. G. Jung; Dorsum: Abraham A. Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi. (Wikimedia Commons)

Freud on his visit to Clark University in the United states, 1909. Front, from left to right: Sigmund Freud, G. Stanley Hall, C. G. Jung; Dorsum: Abraham A. Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi. (Wikimedia Commons)

The utilize of a biological theory in society to explain psychological phenomena indicates another feature of Freud's theories that was typical of the nineteenth century: the use, in psychology, of scientific paradigms which are not proper to psychology, but to other scientific disciplines. For case—and this is particularly evident in Freud'southward primeval, never completed work, his Projection for a Scientific Psychology —Freud understands the mind as a organization in which discrete quantities of free energy increase and decrease, in which the overall quantity of free energy in the arrangement remains constant, every bit well as a arrangement in which, in lodge to ensure that continuance, quantities of energy can move from one part of the organization to another. Freud here is applying models taken from physics, and peculiarly discoveries in nineteenth-century thermodynamics, to the operations of the mind. Freud'due south readiness to apply models from physics to the heed additionally explains his conviction that psychological events are as open to a complete causal and deterministic explanation every bit the events which natural sciences, like physics, chemistry, and biology, explain.

Freud's idea is not only involved in the historical currents in which it adult; it also has its own history. Freud'due south Five Lectures was written in 1909 as a serial of lectures to be delivered at Clark University in the U.s.a.. (A famous anecdote—perhaps not true—is that Freud, upon arriving to America, said, "We are bringing them the plague.") This text is a summary argument of the basic ideas that Freud developed in first period of his idea: the significance of the conflict between a censoring consciousness, and sexual desires attached to memories which, because they are censored, become repressed and unconscious; the function of infantile sexuality in determining the content of those censored memories and desires, and in item the role of the Oedipus complex—the child's sexual desire for the parent of the reverse sexual activity, and rivalrous aggression toward the parent of the same sex activity; the special identify of dreams as a central, or "regal road," to the decoding of unconscious memories and desires; and the necessity for a therapeutic do of interpretations, in which symptoms of mental pathology can be taken as signs whose subconscious significance are these memories and desires.

In the ensuing years, Freud'southward thought took new directions, guided by new discoveries. Civilisation and its Discontents , published in 1930, relies upon these. Freud developed the second topology, or the structural theory of the mind: the heed is divided into three dissimilar agencies, a superego—the repository of a person'due south moral ideals, but also the source of a person'due south moral cocky-criticisms and, crucially, the source of a person's guilt; the ego—a person'south "I" or self, which is responsible for the perception of reality, organizing thoughts into a coherent whole, as well equally adjusting actions so that they adapt with a person'south moral demands and desires; and the id—the locus of a person'southward unconscious desires and memories. Additionally—and it is noteworthy that this developed occurred after the first Globe War—a new emphasis is placed on the psychological role of aggression and decease. Freud proposed a dualistic theory of the drives, according to which the power of eros , or love, is in disharmonize with the power of thanatos , or death: a subversive, aggressive force which is directed toward other people, but also toward the person herself. Civilization and its Discontents focuses on the origins of the superego in human civilization, the aggression that the superego controls, simply also the aggression that the superego breeds, and, ultimately, the psychological problems which this aggression poses. The homo is an unhappy brute: merely not only because its sexuality is unconscious and repressed, but also considering, in its very state of civilization or civility, it is ambitious and destructive.

Source: https://www.college.columbia.edu/core/content/writings-sigmund-freud/context

0 Response to "Describe the Freudian Revolution and Its Impact on the Arts"

Enviar um comentário